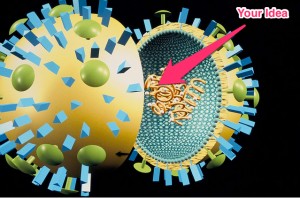

One of the great discussions over the weekend at BarCamp News Innovation/Creation Camp, Started by Greg Linch from the Washington Post was about how ideas spread, and discussing what elements might exist to make something go “viral”. There was another interesting post that came across my desk this morning from an education blogger, about Making Learning go Viral. What is it with “virality?” Seth Godin wrote about it in his book, Unleashing the Idea Virus back in 2000 (You can download a copy for free here)and we’re still talking about it, almost 15 years later, but people are still wandering around talking about the viral (insert noun here) and surprised by its effect.

One of the great discussions over the weekend at BarCamp News Innovation/Creation Camp, Started by Greg Linch from the Washington Post was about how ideas spread, and discussing what elements might exist to make something go “viral”. There was another interesting post that came across my desk this morning from an education blogger, about Making Learning go Viral. What is it with “virality?” Seth Godin wrote about it in his book, Unleashing the Idea Virus back in 2000 (You can download a copy for free here)and we’re still talking about it, almost 15 years later, but people are still wandering around talking about the viral (insert noun here) and surprised by its effect.

Seth spoke about one of the most important factors in spreading an idea virus is to count on sneezers- the very connected among us, who love to pass around ideas, just like someone who might sneeze without a tissue passes around a cold, accidentally or on purpose. Sneezers come in two varieties, according to Seth- Promiscuous sneezers who can be motivated by money and the like- while not well respected often for their own opinions, they are still really effective at spreading ideas through their networks online. Then there are the powerful sneezers- the people you would love to hand your ideas off to, knowing if they like them, the social proof they bring means your idea might really have a chance of taking off. This could be an influential blogger, a newspaper or TV person, a celebrity, the local head of the PTO, or politicians or lobbyists. These should be people from whom you can’t buy influence (real or perceived) because everytime their default credibility ebbs just a little bit, to paraphrase Seth.

The other key points you should read in Seth’s book include attracting promiscuous sneezers and the lifecycle of a virus, but I’ll let you read that for yourself.

In the end, the whole point is that things will have a better chance to go “viral” if you have somethign that’s worth the attention invested into it, and the access to the idea is easy. With social channels and social share buttons, there’s a better chance than ever before that your idea could be spread, but there’s more competition as well, making the marketplace more crowded than it was back when Seth first started talking about the idea virus.

More interesting to me is that if ideas spread like a virus, or even as one physician in our session suggested, more like cancer, gradually replicating itself until a mass of a certain size developed, allowing it to spread and metastisize, is how can we stop the spread of ideas? For cancer, we give a variety of drugs that act as poison for ideas, or the angiostatins, which cut off the blood supply to a tumor. How could we do the same thing to bad ideas or lies that become memes?

Can We Kill Ideas?

I’m not sure we’ve figured out how to do this, in part because the initial spread of an idea often involves many exposures to the idea, and the more it’s repeated, the more people come to think of it as true, even if we find out later, it’s not. Think how many people still believe Barak Obama was born outside the country, and you get the drift, or how smart and important people convinced themselves Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. Even when we know these things aren’t true, it’s hard to even craft a sentence that doesn’t reinforce the idea. (When you say “X believes _____ and it’s wrong”, people hear the wrong idea, and it is reinforced. Even if they hear the disclaimer, it still reinforces the original bad idea.)

Add onto the problem that we have a 24 x 7 news industry, online and on air, that needs to talk about something. I saw some of the most insane reporting ever around the Boston Marathon bombings coming from major news channels, because they simply didn’t have anything of substance to add to the conversation. Any tidbit they thought they had could be magnified out of proportion, and then had to be backtracked later, but the damage of putting out erroneous information has already been done.

I’m not sure we can put the genie back in the bottle. But I sure wish we had a chance to try. What would happen if people cut away from the disaster and instead let the workers and first responders do their job, and reported on it later when more facts were available? Would the rest of the country be harmed by having to exercise a little patience? What would happen if we didn’t rush to judgment or assume immediacy trumped accuracy? I bet it’s worth a try.

Sunlight is a great disinfectant, but like most good public health measures, it’s better to prevent disease than deal with its aftermath. Perhaps one of the best things we can do is to start questioning, or even reading articles before we pass them on, willie nillie. Maybe we all have to become determined to be better informed, and to start holding journalists accountable for information, not entertainment. And that also means holding ourselves to this same standard. You need to double check that that article you are passing along and treating as fact is not an Onion parody. You need to read the whole story, and confirm what you can. You need to have reliable sources you trust, and primary sources at that.

I think the only way we might have a chance of stopping the spread of some ideas is deciding to be part of the cure ourselves. While getting attention and being a source of the fun new thing seems great, in the end, you have to consider whether your sneezes are, on balance, healthy or benign, or harmful in the aggregate.

And I don’t think that’s easy for anyone to determine, but maybe if we all just take a beat before hitting “share”, we’ll be a little better off in the end.

What do you think? What are the ways to stop an idea virus, especially if it’s harmful?

Plug for a favorite book of mine: In order to learn more about how to harness attention, make sure to check out John Medina’s Brain Rules, especially the sections on attention and memory.